Inside Tajimi: Watching a Handmade Watch Come to Life

Alan Birchall and “Pièce d’essai”

There are watchmakers, and then there are the very few who attempt something almost no one else dares anymore: to build a watch — not just finish it — by hand.

Alan Birchall is one of them.

Half French, half English, raised in France, shaped by years spent in Australia, he now lives in Japan. Not Tokyo — Tajimi, a quiet city in Gifu Prefecture better known for ceramics than horology. And yet, the more time I spent there, the more it made perfect sense. Tajimi is a place where people shape things slowly, deliberately, and with their hands.

That is exactly the kind of environment where a handmade watch can exist.

Handmade Is Not Hand-Finished

People often use the word “handmade” casually, when what they’re really describing is hand-finished.

Those two things are not the same.

Hand-finished means a machine creates the part, and then a human polishes, bevels, or decorates it.

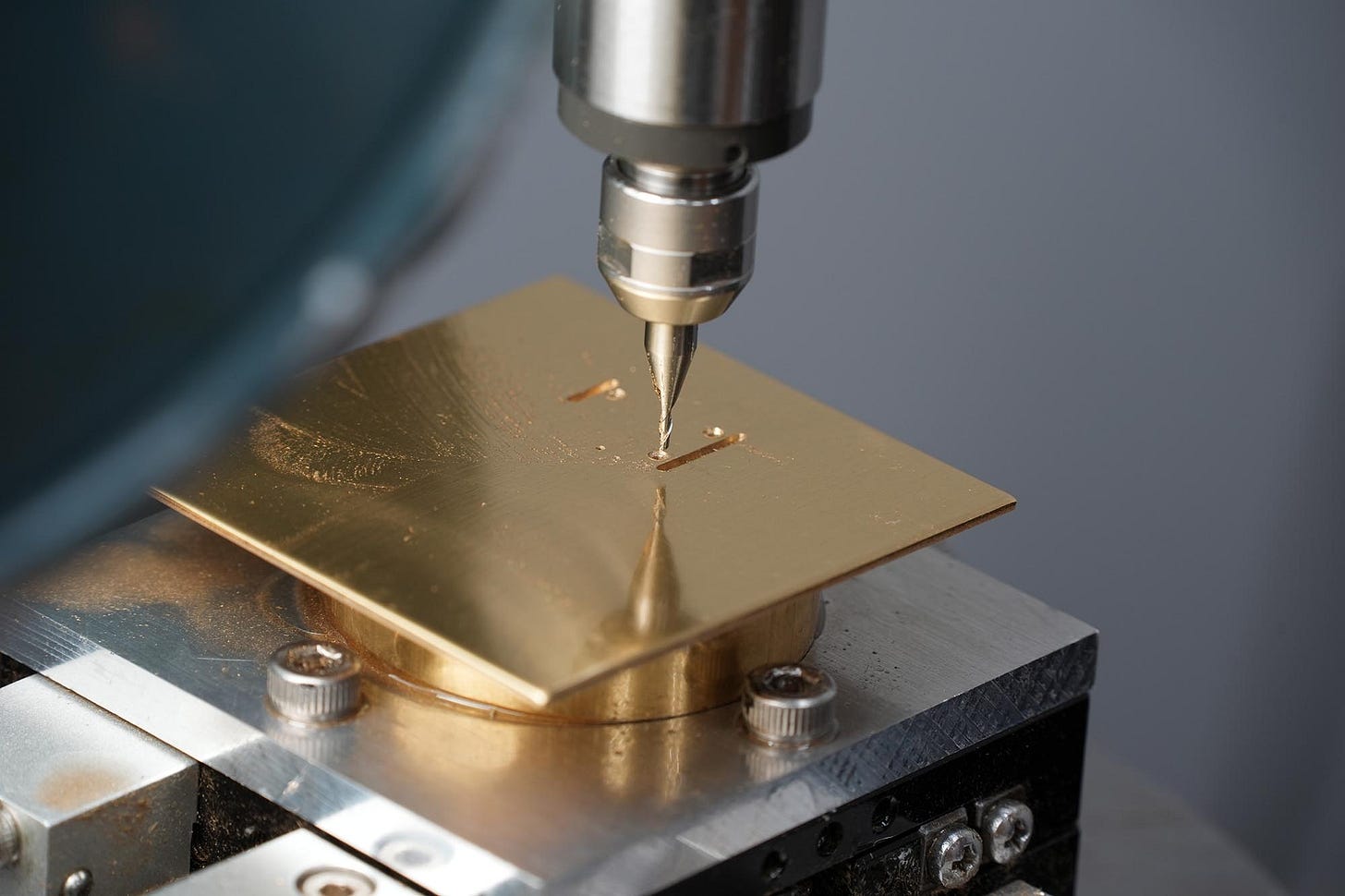

Handmade means the part itself — the bridge, the plate, the screw, the wheel — is shaped by a human being operating the machine manually, guiding each cut, each pass, each angle. No CNC programs, no computer-loaded files, no automation.

This distinction is important because almost nobody chooses the handmade path today. It’s slow. It’s unforgiving. It depends entirely on the skill of one person.

Alan has chosen it anyway.

The Prototype: “Pièce d’essai”

The watch he showed me is his prototype, named:

Pièce d’essai — literally, test piece.

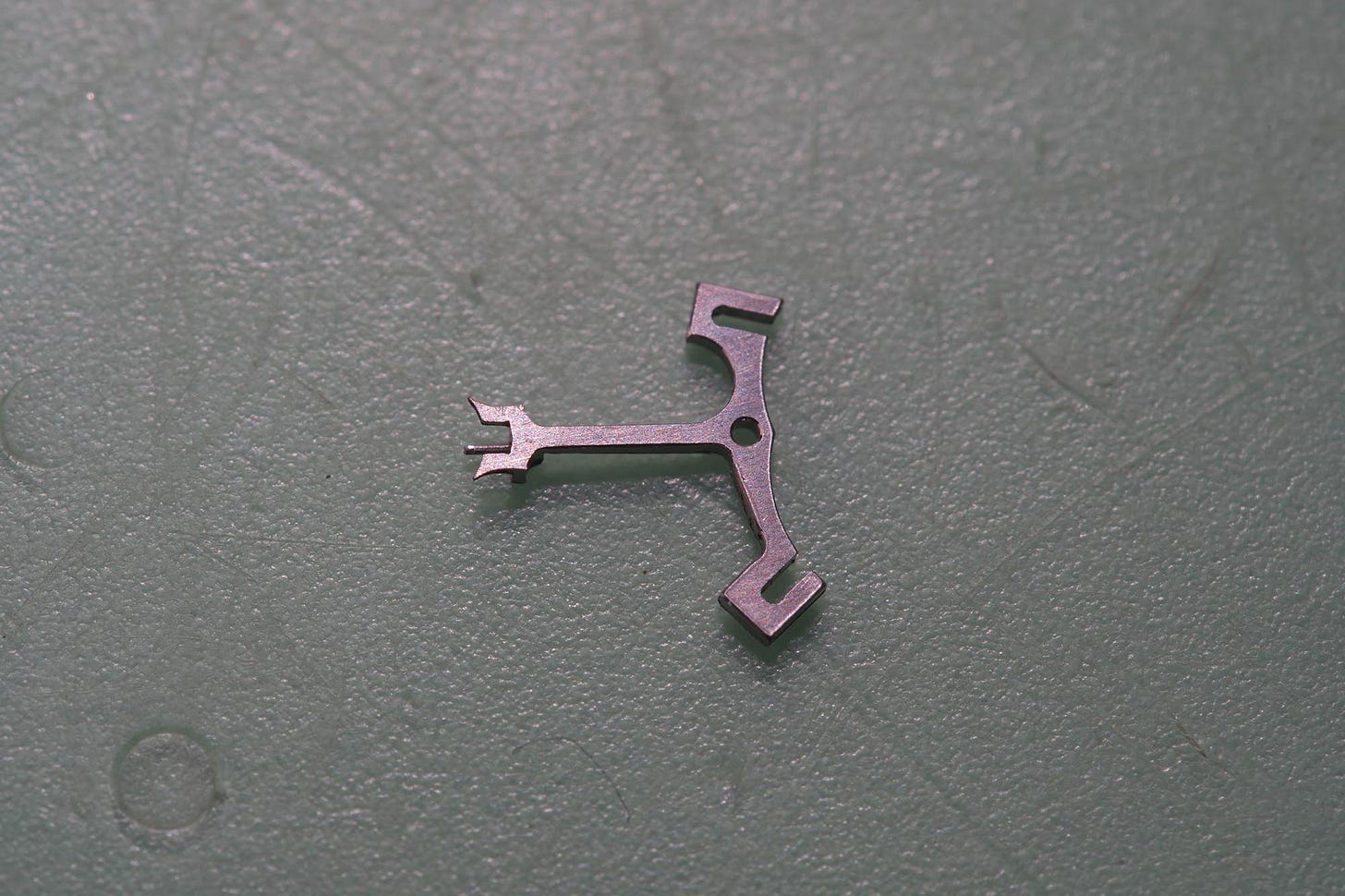

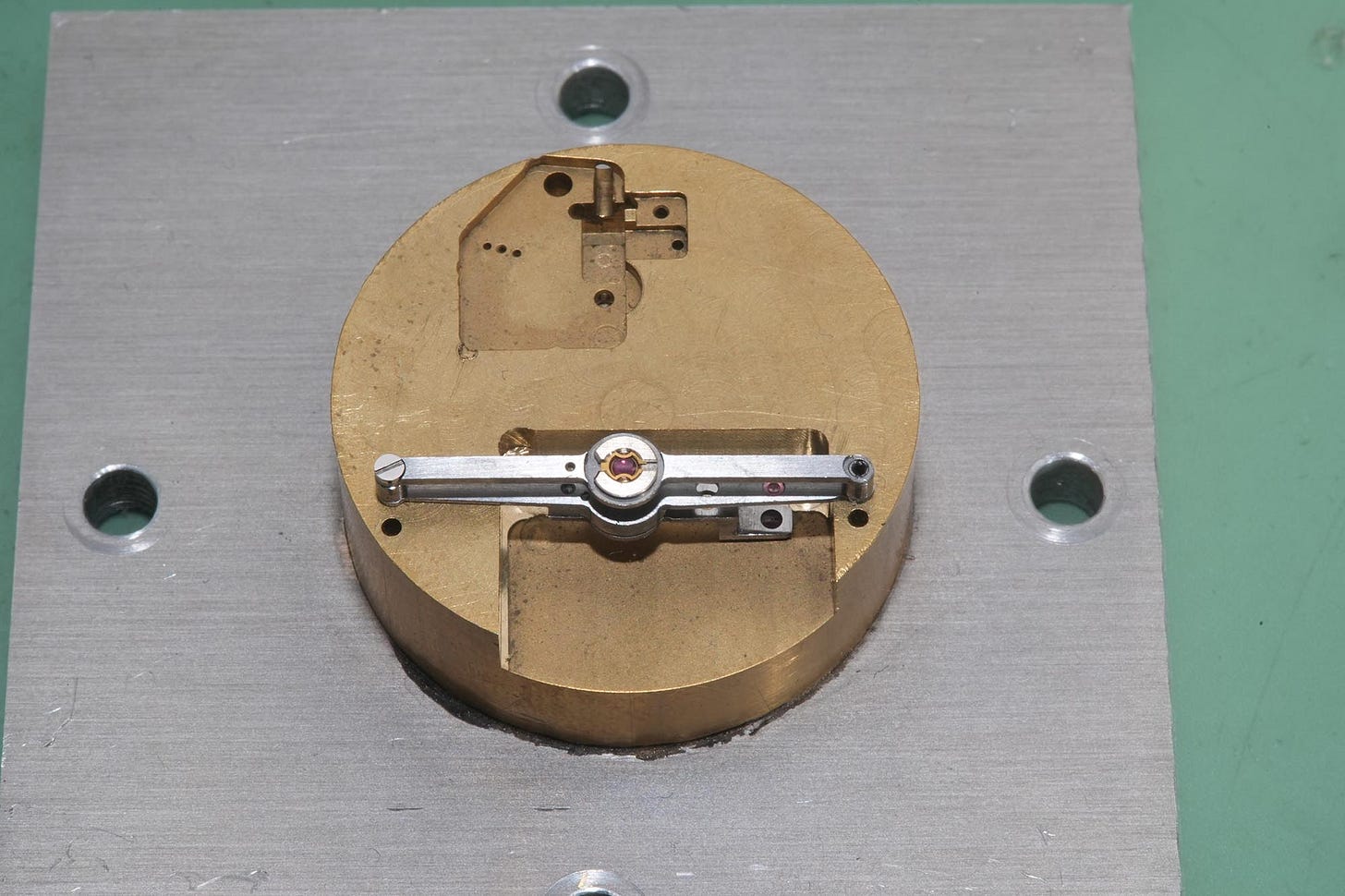

It’s a time-only watch, stripped of a dial.

The full movement is exposed: frosted surfaces, lean architecture, intentional geometry. The case measures 35.60 mm, compact yet commanding in presence.

On this prototype, approximately 80% of the watch was handmade.

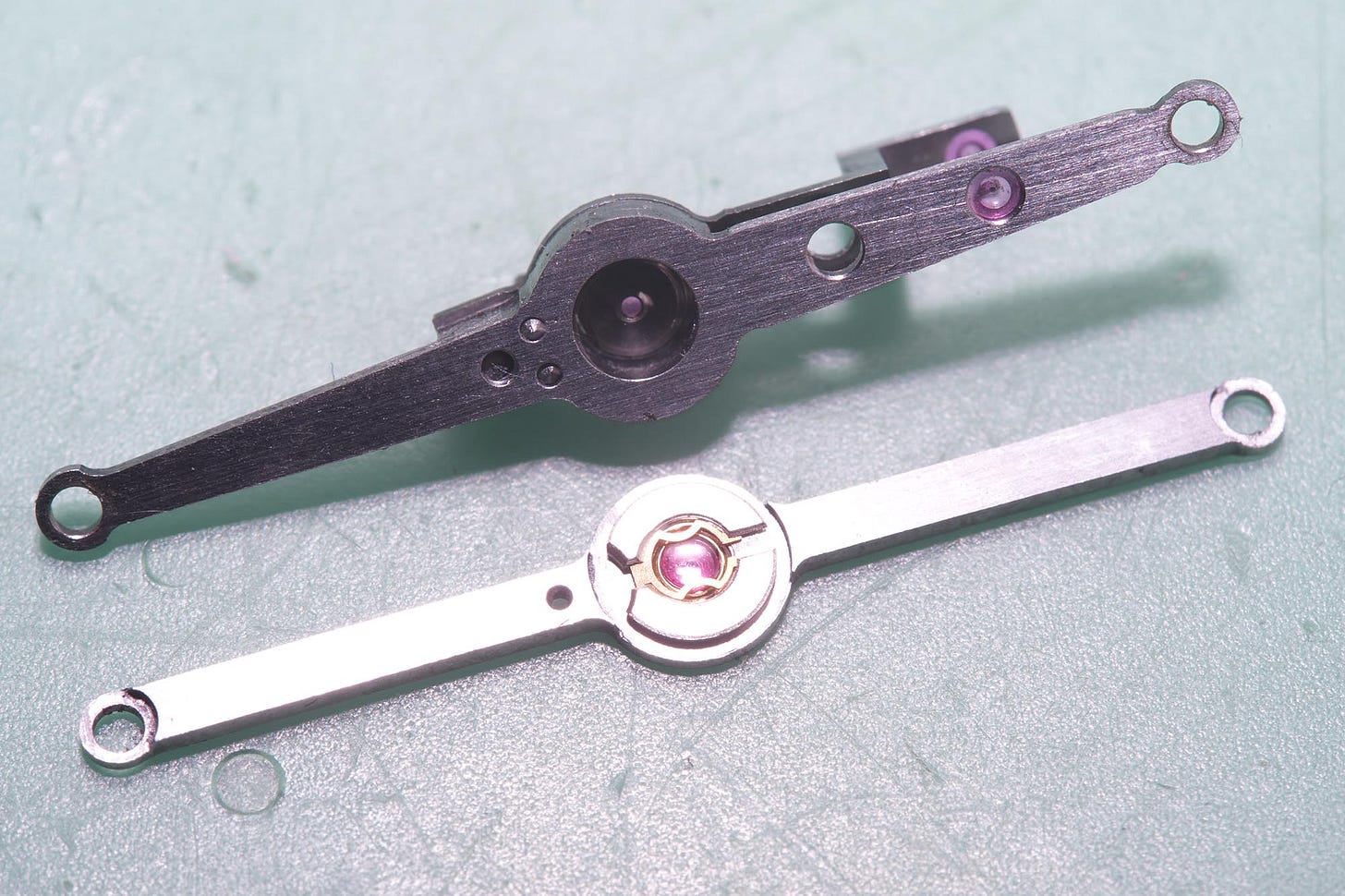

The only parts not made by him were:

The crown wheel

The train wheels (from center wheel to escapement wheel)

The balance staff

These weren’t shortcuts — they were deliberate choices. Custom wheel cutters are expensive, and for a prototype, he needed wheels he could trust to validate the design. Now that he’s satisfied, he’s making those components by hand for his customer pieces, raising the handmade percentage to about 95%.

Some parts will always be outsourced — the same ones every watchmaker in the world outsources:

Crystal

Jewels

Hairspring

Mainspring

Gasket

Everything else is shaped by his hands.

Two and a Half Years of Work

From the first sketch to the completed prototype, the Pièce d’essai took two and a half years.

This wasn’t a full-time project. He worked on it around life, around responsibilities, around teaching himself things most watchmakers simply buy.

The number of total hours doesn’t really matter.

What matters is the dedication.

Machines with Quiet Histories

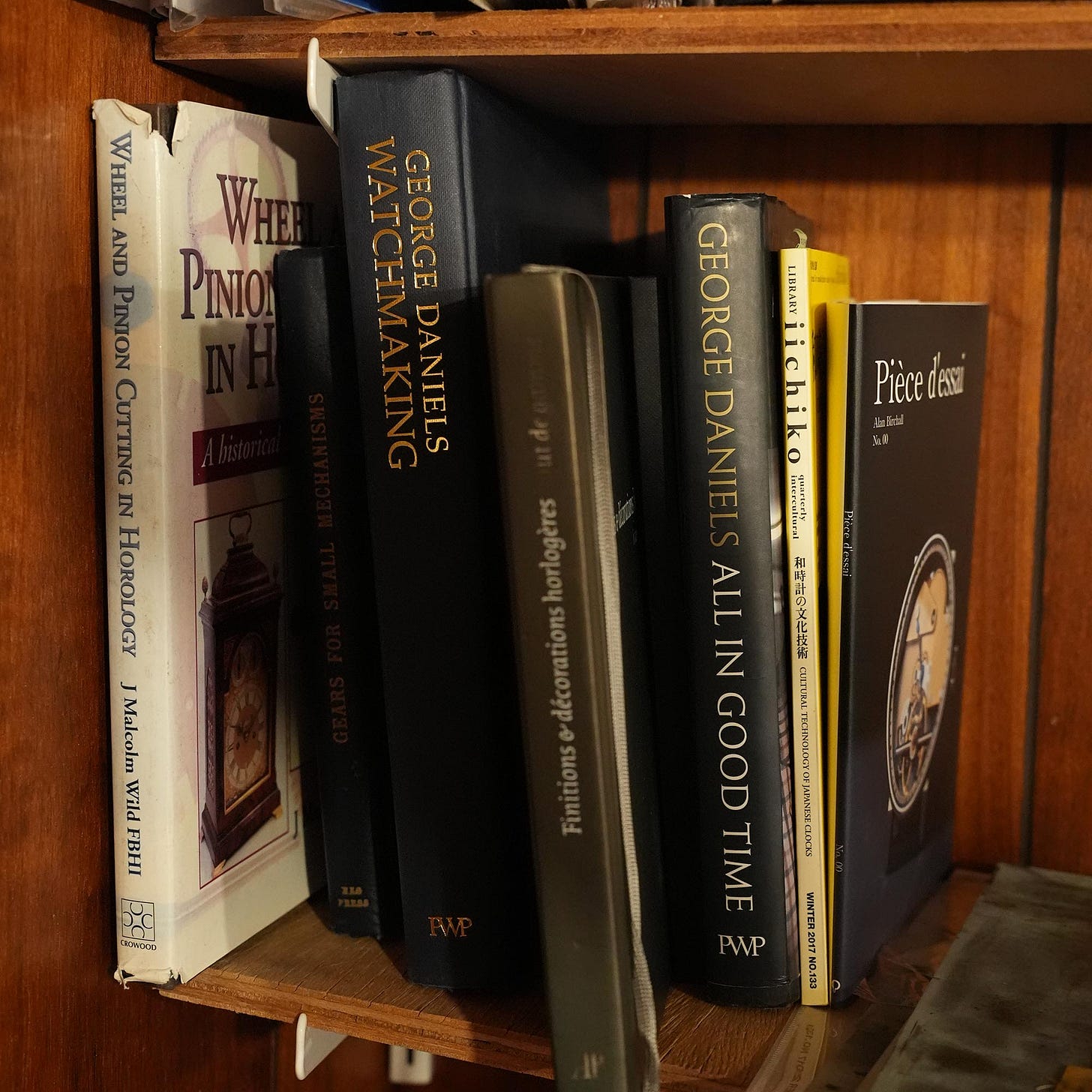

Alan’s workshop is filled with character — old machines with stories attached, even if the stories aren’t fully traceable.

Most of his machines are from around the 1970s, bought from second-hand dealers in Japan. One dealer told him they came from an old Seiko factory, but the nameplates were stripped, so nobody can confirm it. Still, they’re unmistakably Japanese watchmaking machines

.His SIP jig borer, Swiss-made in the ’70s, came from another dealer in Tokyo who said it was used to make plastic mould prototypes for toy car figurines. Again, impossible to verify — but it adds charm to the workshop.

These machines have lived other lives before ending up in a small house in Tajimi, now helping shape one handmade watch at a time.

A House Shared Between Two Crafts

Alan didn’t only find watchmaking in Tajimi — he met his wife there too.

She is a ceramics artist whose works are sold through galleries, and their home is a living portrait of two crafts coexisting under one roof.

The house is divided into two halves:

Her Side: The Ceramics Studio

A large, rustic space dominated by a massive kiln. Clay dust on the floor. Tools aged by repetition. Shelves lined with organic, earthy forms. It feels warm, grounded, shaped by soil and fire.

His Side: The Watchmaking Workshop

Silent. Precise. Controlled.

Old machines arranged with care. Brass and steel sorted meticulously. Movement parts laid out like instruments in a laboratory. If her space is shaped by intuition and force, his is shaped by microns and focus.

Two crafts. Completely different. Yet perfectly complementary.

They work separate hours, each following the rhythm of their respective materials — clay for her, metal for him — but they are united by the same philosophy:

to create something meaningful by hand.

Seeing the two studios side by side was like stepping into a dialogue between fire and steel, between rustic imperfection and exacting precision.

Life Beyond the Workbench: A Small Farm

During my visit, Alan took me to the small farm plot he tends in the Japanese countryside. He grows carrots, garlic, pumpkins — simple crops, but grown with care.

These plots are often unused farmland that landowners loan out to keep the soil active. Alan works the land with the quiet confidence of someone who knows how to farm. His grandparents were dairy farmers, and those early years gave him an intuitive understanding of agriculture.

Watching him walk across the rows of vegetables was strangely revealing: the patience needed to farm is the same patience needed to build a watch by hand.

This is what makes Tajimi feel right for him.

It is a place where you can work with the land and with metal, with time and with nature.

Seeing Him Work

He showed me part of his process.

He couldn’t show everything — nobody could, unless I stayed for a year — but he showed enough:

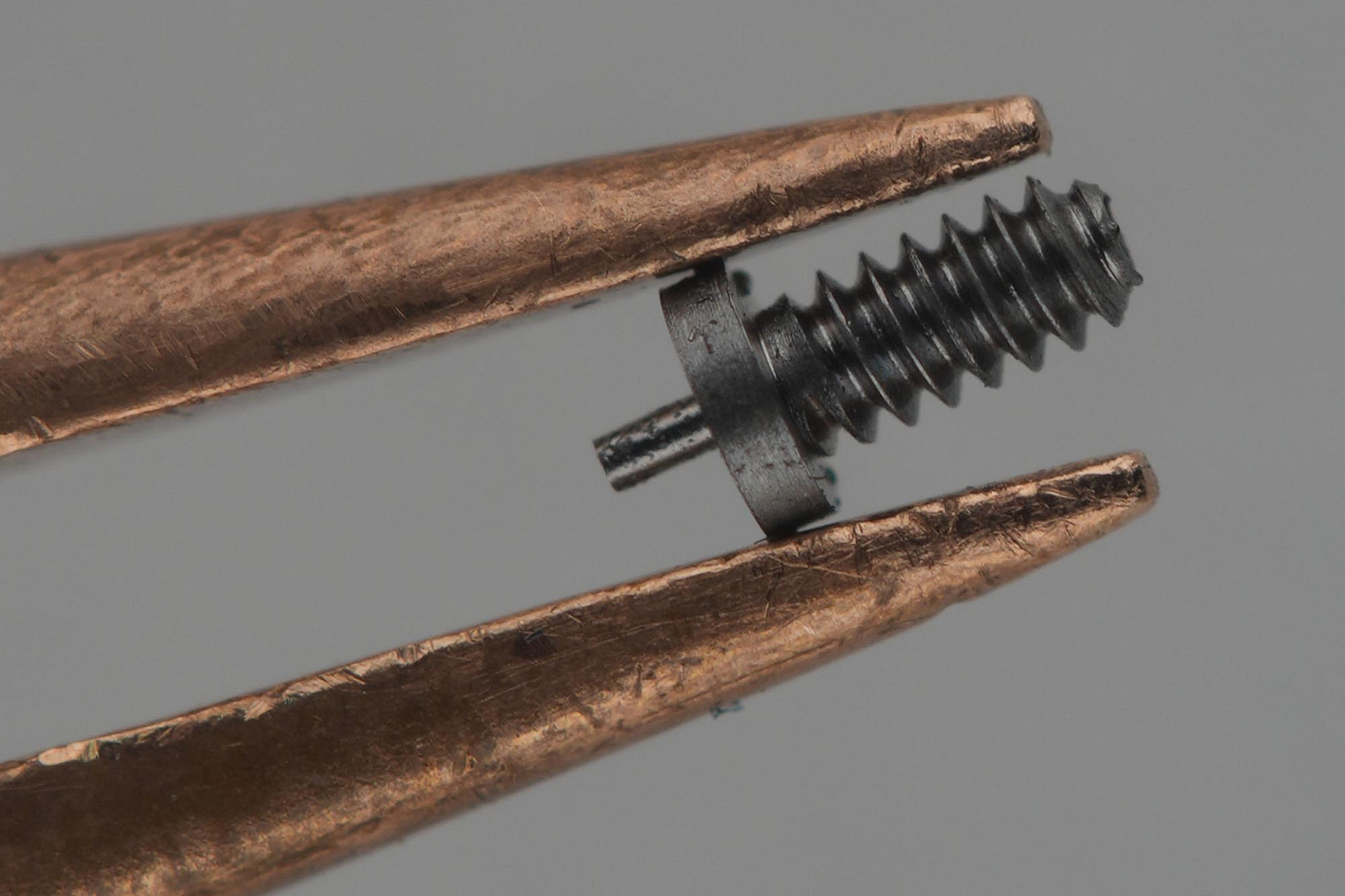

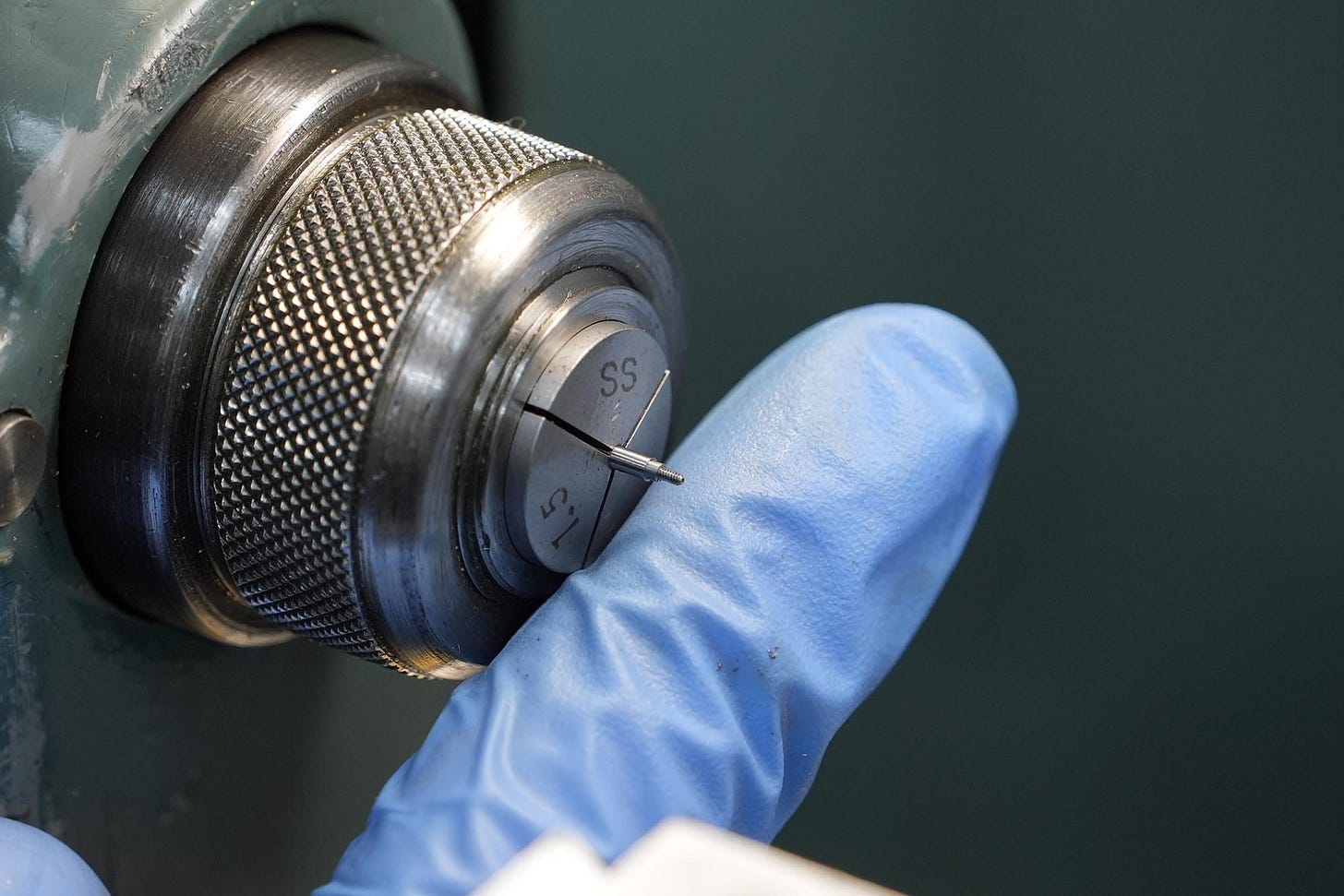

He made a small setting bridge.

He made a screw.

And what struck me was not the machining itself, but everything before the machining:

Measure the raw material.

Check the measurements.

Adjust the machine.

Change the tools.

Reset the alignment.

Start again.

Then silence.

Pure concentration.

Forty minutes later — a single screw.

The next screw would be faster, but only marginally.

Nothing in his workshop is automated.

This is the true definition of handmade

The Price and the Wait

A watch from Alan starts at ¥13,000,000 JPY, with higher pricing for custom modifications.

The wait time is 12 to 30 months from the deposit, depending on complexity and the rhythm of the workshop.

Considering what he’s doing — and how few people can do it — these prices will inevitably rise as his craft becomes better known.

What Comes Next

When I asked about complications, he smiled and said:

“Handmade is already a complication.”

He isn’t chasing tourbillons or perpetual calendars.

Instead, he’s focused on:

refining his process,

increasing the handmade percentage,

improving efficiency without losing soul,

and offering custom modifications based on the current design.

His work evolves through iteration, not expansion.

Each watch is not a model — it’s a chapter

A Beginning, Not an Ending

This visit wasn’t just about seeing a workshop.

It was about stepping into a life built around patience, craft, and intention.

Tajimi may be known for ceramics, but in a quiet house split between a giant kiln and old watchmaking machines, something remarkable is happening — something vastly rarer than most people realize

This is just the beginning of the story.

And there will be more to tell.